Ninety per cent bored stiff, nine per cent frozen stiff and one per cent scared stiff.

That was - historian Andy Robertshaw insists - the experience of most soldiers in the First World War.

It was not one of constant fighting, never-ending trench foot and heartless aggression from commanding officers, despite the impression to the contrary given by most film depictions.

As for how I felt on a chilly but sunny day last week when I toured Andy's faithful reconstruction of a real British trench, I will let you decide from the pictures.

The trench dug in woodland at Detling Showground in Kent is very much not his first rodeo - there have been three other iterations, the first of which was in a field next to his back garden.

But his current one - which was dug in 2021 and is a reconstruction of a section of the line at Railway Wood at Ypres in Belgium that was operational between 1915 and 1917 - is by far the most extensive.

It is not just the trench that is an accurate reconstruction, my uniform and kit was too.

Sourced from Andy's own 'prop house', my shirt, tunic and trousers were - as their scratchiness attested to - woollen, whilst the vest was cotton.

Having politely declined the chance to replace my boxer shorts with cotton drawers (that's underpants to younger readers), I was then laden with kit, which altogether weighed around 70lbs (32kg).

The hefty webbing boasted a water bottle, a spade-like entrenching tool, bayonet, 150 rounds of ammunition and a haversack with the likes of mess tin, cooker, food rations, cutlery, comb and razor inside.

Around my legs I had my puttees, the lengths of fabric designed to stop mud getting into your boots and to support your calves on marches.

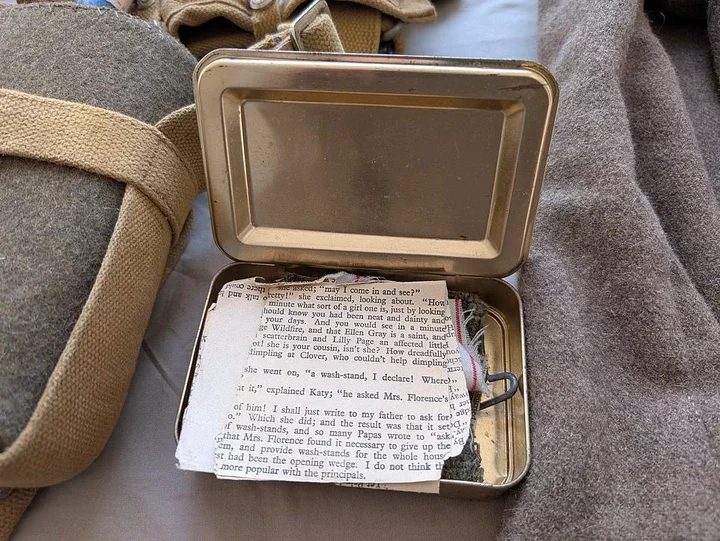

In my pockets I had an original but deactivated grenade, plus a tin with kindling and - try not to wince - scraps of newspaper that were used as toilet paper.

My most important bit of kit - besides the cigarettes, leather boots and gas mask - was of course my rifle, which I was slightly disappointed to learn was a well-built replica incapable of doing any harm to Jerry or anyone else.

Once fully suited and booted, I felt newly powerful as Sergeant Howard of the Royal East Kent Regiment, known as The Buffs.

Andy, who turns 69 later this month, is not just a war-obsessed eccentric.

The former head of education at the National Army Museum, he is a hugely knowledgeable expert with more than a dozen books to his name.

He has served as a military advisor on films including Steven Spielberg's War Horse, Sam Mendes's epic 1917 and, perhaps surprisingly, 2017 superhero film Wonder Woman.

In the former, which was released in 2011, he also had a small on-screen role as the gruff sergeant who blows the whistle before troops go 'over the top' to their doom.

And then there are his beloved trenches. He built the first next to his home in Surrey in 2012. By 2018, he had a one-acre network at a farm near Canterbury in Kent.

When it became clear the site was 'not working', he says, he searched for a new home for a bigger, better trench.

In 2021, he set up the Centre for Experimental Military Archaeology (CEMA), based in Detling.

Their first project - which took around a month to complete using the help of JCBs and an army of volunteers - was the current trench.

The set-up lives off people - mostly groups of schoolchildren - coming to see it to learn from Andy and his team what life was really like in the trenches.

The latest open day, when the trench site is open between 10am and 4pm, happens to be this weekend.

Andy is on a mission to accurately represent the reality of life for most First World War soldiers, men who 'eat, sleep, drink and go to the toilet'.

'What we see on the big screen is 1 per cent of the war,' the historian says.

'We don't see the 99 per cent of boredom and digging and building and living and existing in a hole in the ground.

'That's what we try and do. We're a 99 per cent organization. We leave the one per cent to the imagination.'

The trench itself is the kind of thing that youngsters might dream of building on their parents' manicured lawn.

It is a warren of sandbags, corrugated iron, lookout posts and hand-drawn signs.

There is a latrine for doing the obvious, a small, bare shelter ironically called 'The Ritz' and a 'tiny sleeping space dug into the side of the trench that would have been known to troops as a 'funk hole'.

Lined with wood, it was, as I discovered when I rather awkwardly climbed in, extremely uncomfortable.

In fact, nothing in the trench was about comfort. It was all about function and survival.

New arrivals would have gotten to the trench at night to relieve comrades who had been there for five days.

There would be one man on guard duty, standing with bayonet fixed with his head and shoulders above the parapet.

Nothing was allowed over the ears, even in cold weather.

The morning would start with a rum ration and then breakfast, which often involved bacon.

Rations also included corned beef, meat and veg stew, butter, condensed milk, oatmeal, rice, tea and cigarettes.

'The problem with the food here is it's boring. It's almost identical every single day,' Andy says

'All soldiers are hungry all the time because they don't know when the next meal is going to come,' he adds.

'So what's going to drive you is your pocket contents. Do you have your bog paper?

'Do you have a bar of chocolate? Do you have a box of matches? Do you have your cigarettes?'

During daylight hours, there would again have been one man on lookout.

Others in the trench would be doing their best to get some sleep, until woken for their turn on sentry.

Troops also had to contend with the threat of a gas attack and the constant spectre of the cold.

In winter, troops would be issued with a great coat, but there were no blankets or sleeping bags.

Meanwhile, in my role as a sergeant I would be doing my best to care for those junior to me.

'What holds the unit together, isn't the hatred of the Kaiser or love of George V, it is the fact that you as a sergeant look after the men,' Andy says.

'Have you got everything you need? Has the mail arrived?

'In movies, NCOs [like corporals and sergeants] are always shouting, in reality, they're going to be much more successful if they're saying, have you had letter from the wife? How did the match go on Saturday? That kind of thing.'

He adds: 'It's all to do with basically, staying alive.'

Next to the trench is a small section of railway. The real thing would have been laid by men from the Royal Engineers.

It supplied the likes of food, water, ammunition, building supplies, sandbags and timber to the front line.

Going the other way would be the wounded. The dead were buried close to where they fell.

The men at Railway Wood were involved in the First Battle of Ypres in late 1914; the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915 and the Third Battle in 1917, better known as the Battle of Passchendaele.

In the latter battle alone, more than 250,000 Allied troops killed, wounded or missing. It was fighting defined by horrifying cost for little gain.

The sobering reality makes me feel rather silly, even if I do look the part in my authentic uniform.

Our final stop before I walk back into the 21st century is the reconstruction of the dug-out, which would have been around 30feet deep and reserved for officers.

Andy's version is, for health and safety reasons, in an above-ground structure nearby.

I pose for a photo at the dinner table and on the side of the bunk beds, as candles provide a flicker of light.

It is a fitting end to my fleeting experience of life in the trenches.

Andy, who lives in the nearby village of Faversham with his wife Janice, is focused on authenticity.

'When you look at trench warfare, the people in the trench are probably talking about how the local football team did on the previous Saturday, rather than going, "oh, you know, should I write some poetry or just die a bit?"

'Without being cynical, I like to think that they were like us human beings, and that their lives were bounded during the day by sandbags and the sky.

'But actually, what they were were people waiting for the war to end so they could go home and pick up the threads of their lives, as my granddad did.'

Andy's grandfather, John Andrew, survived a gas attack as a soldier in the First World War. Tragically he died from prostate cancer aged 66.

'I suppose what drives me is that from being a little boy growing up in Suffolk, mum ran a Sue Rider shop,' Andy continues.

'She brought back, 50p a pop divisional and regimental histories, and I just devoured them and wondered at the time, was Suffolk anything like the Somme?

'And then then I got to go there and spend time there.'

Only earlier this month Andy was back in France to guide a family who lost a relative on the Somme.

This weekend, he will be hard at work giving visitors a tour of his trench.

In the past four years, thousands of schoolchildren have visited to learn about the reality of the Great War.

Andy hopes that many thousands more will come in the future.

As for my time being Sergeant Howard, I feel a little wistful as I take off my uniform and hand it back.

Comments