Key Takeaways

Teaching your child about four foundational emotions-anger, sadness, fear, and jealousy-can help them build a lifelong emotional vocabulary.

-

Naming and normalizing feelings gives kids the language they need to express themselves without shame or meltdowns.

Use books, real-life examples, and open conversations to help your child recognize emotions in themselves and others.

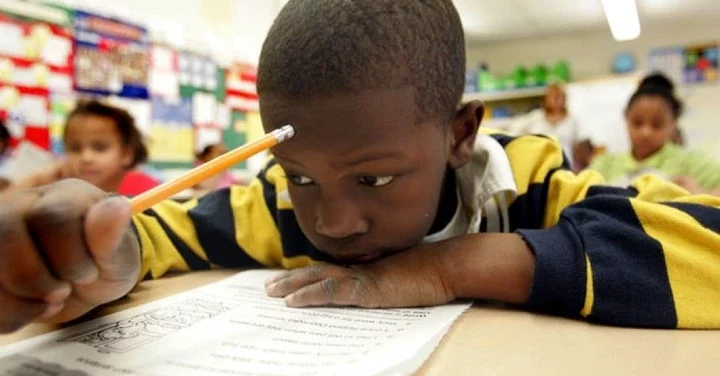

We all know that little kids can often experience big emotions, and they begin to show those feelings as early as their first birthday. That's why it's so important to know how to talk about emotions with young children-it helps them begin to understand the complexities of their own feelings. In fact, learning to identify and express emotions is just as important as the academic lessons they'll learn in school.

The purpose of emotions is to help us make sense of what's going on inside and around us. Feelings offer quick feedback based on our past experiences. But for young kids, those experiences don't exist yet. They respond to situations based on how they feel in the moment.

Rather than overwhelming your child with a long , start with the basics. Ahead are four of the most common big emotions-which all other emotions stem from-and how to help your kid recognize and talk about them.

1. Anger

Anger is a strong feeling of annoyance, displeasure, or even hostility-and contrary to what many are taught to believe-anger does not have to be a negative emotion. It's an emotion just like any other, and talking about it can help kids gain a better understanding on how to manage it.

For kids, anger often shows up when something doesn't go their way-like when a playmate grabs their toy. Their fight or flight response kicks in, and because they haven't learned to , they may lash out by hitting, yelling, or having a meltdown.

"Anger may seem irrational, but for a child that hasn't yet learned how to regulate emotions, it's an immediate natural reaction to some sort of wrongdoing your child feels," says Jaclyn Shlisky, PsyD, a licensed clinical psychologist in Long Island, New York.

Instead of reacting with punishment alone, talk it through with your child as it's happening in the moment so they can learn to name the emotion.

Step One: Identify the feeling

Say, "It looks like you're really mad," and mirror an angry facial expression so they can connect the word with the feeling. Be mindful of your language, it's important to not use definitive words like "I see" over words like "It looks like" or "It seems."

Jaime Gleicher, LMSW, a behavioral therapist at Harstein Psychological Services Center, points out that it's crucial you don't put exact words on an experience and invalidate your child's feelings if the child isn't actually mad, rather feeling sad or anxious. "It gives the child the opportunity to correct the parents if it isn't so," says Gleicher.

Step Two: Explain the feeling

Say, "Sometimes things don't go the way we want them to and that makes us feel mad and upset." Then, teach your child how to express those feelings in words instead of actions.

Have your child practice saying something like, "I really don't like when you grab a toy out of my hand." Gleicher explains that negative behaviors-like hitting, yelling, or crying when feeling angry-is the underlying emotion that has not been regulated or recovered yet. A meltdown is the outward expression of a misunderstood emotion. Your child needs help identifying how they are feeling because they can't communicate it on their own. That's called building your child's emotional vocabulary.

"They need a word to associate with a feeling so they can use their words to express rather than react," Gleicher explains. When your child throws a tantrum, hits, or does something inappropriate, she recommends asking them how they're feeling, while providing a logical consequence. That way, they begin to understand that anger can lead to hitting, but there are other ways to deal with anger that don't involve hurting others.

"The message should always be: you have feelings, this is how they look, it's OK to feel and no emotion is ever permanent," she says. (And don't forget to talk about the positive stuff, too. For example: "You just scored a goal in soccer! How do you feel?")

Step Three: Make things easier

A helpful way to teach kids emotions is by pointing them out in others. "When you read storybooks or watch movies, ask your child how they think the character may be feeling? This not only increases emotional vocabulary, it teaches empathy, the act of putting oneself in others' shoes," says Gleicher.

2. Sadness

The feeling of loss, sorrow, or being let down is a major one for your kiddos. Sadness can happen when a child is scared, misses someone, , or is going through something stressful (like hearing their parents argue or missing a long-awaited playdate).

Sadness often develops through disappointment. Kids struggle to regulate their emotions when they feel disappointed, leading them to experience sadness.

Step One: Identify the feeling

"When your child is sad they not only feel sad, they think sad and will act sad," says Dr. Shlisky. Tears are often the most obvious sign, but sadness may also show up as anger, isolation, or clinginess.

"By the time they turn 1, infants gain an awareness that parents can help them regulate their emotions. They cry and you come running. As they grow out of the infancy stage, toddlers begin to understand that certain emotions are associated with certain situations," says Dr. Shlisky.

The danger of sadness and not understanding its underlying source is that sadness can turn into anger and then result in meltdowns. If every time your child cries you try to appease them, you're just putting a bandage on a situation instead of helping them solve a problem." Children need the tools to be able to say, "I feel sad because..." otherwise they are learning their feelings can be muted and they won't learn how to name the real reasons for their sadness, adds Dr. Shlisky.

Step Two: Explain the feeling

Say your child loses their favorite stuffed animal and is feeling sad, don't rush to distract them or shut them down. Instead, sit with them, offer hugs, comfort, or just a quiet moment to cry things out.

"You may also normalize their feelings by sharing a story about how you experienced a similar loss when you were their age. Be honest about how sad you were and how you cried. Talk about what helped you with your sad feelings. Parents often try to be strong for their children, to show them that everything will be OK. However, it can actually be beneficial for a child to see adults showing appropriate emotion. It is OK to say, "Daddy is sad, too." Dr. Shlisky recommends demonstrating that feelings are not something they need to try to mask or feel ashamed of.

Step Three: Make things easier

Avoid the pitfall of telling a child to "use your words" when they're upset. It may seem helpful, but it's not always a realistic expectation-especially when a child is still learning how to connect physical sensations in their body to emotional language.

"I tell a lot of parents to create a feelings chart using emojis which all kids love-and use it to teach your kids to recognize how facial expressions correlate to feelings," says Gleicher. If your child doesn't have the words to describe what they're feeling, they can point to the expression that matches it.

3. Fear

While children aren't born afraid, feelings of fear stem from anxiety and worry. "When young kids have fear it involves some level of perception about danger," says Gleicher. Some fears are developmentally expected-like a fear of strangers, the dark, and being separated from their parents.

But having carefree days every day isn't the norm. Your child might have heard something on TV, seen something or someone that made them feel uncomfortable, or a real-life event spooked them like a car accident.

Step One: Identify the feeling

There are some fears we can't always protect our kids from-like global events or scary headlines. In these moments, it's important to validate your child's worries about the situation ("That does sound really scary") rather than downplay how they're feeling by telling them everything will be fine.

"Be calm and matter of fact in your delivery so your child feels safe," says Dr. Shlisky.

Step Two: Explain the feeling

You can also model empathy by saying, "I feel that way too sometimes," and encouraging your child to ask you any questions about it. And if you don't actually know the answer? It's best to say you will find ways to learn more and get back to them with an answer.

Sometimes, simply allowing your child to verbally process what's going on in their head will help. "At times our kids need to tell us things simply because they're too heavy for them to hold onto by themselves," she says. Helping your that there is an open door and a listening ear anytime they need it can be the comfort they need.

Step Three: Make things easier

For younger children who struggle to explain the root of their fear, telling stories, acting out situations, or reading books about a particularly scary situation can help. Experts recommend books like, The Color Monster and Wemberly Worried to help start those conversations.

4. Jealousy

The green-eyed monster of jealousy has a way of getting the best of us, with it showing up in infants as young as 3 months old, says Francyne Zeltser, PsyD, a psychologist based in New York. It's an emotion easily felt and often expressed-mom holds a stranger's baby or a sibling gets presents for a birthday-but the concept of jealousy is tricky to explain.

While it's often described as feelings or thoughts of insecurity, fear, or concern over a relative lack of possessions or safety, it can also be the feeling of inadequacy, helplessness, or resentment. "Feelings of jealousy are often rooted in an individual's needs not being met. It may develop from a lack of trust and often leads to a sense of insecurity," says Dr. Zeltser.

Difference Between Envy and Jealousy

Jealousy and envy are closely related, but slightly different. With envy, you want what you never had ("I wish I had her bike"). With jealousy, you feel threatened by the loss of something you do have or at least believe you have, like love or attention.

Step Two: Identify the feeling

Material jealousy often appears in toddlerhood. "Toddlers don't think twice about taking a toy they want from a playmate. Luckily, once children are enrolled in school and start understanding societal norms, they usually stop stealing what they want from their peers-but that doesn't stop them from wanting or yearning for the goods other kids have," explains Dr. Zeltser. Try to shift the focus away from material goods and onto the non-monetary riches your family provides. Perhaps you're able to spend more time with your kids because of your flexible work schedule. Point out the positives so you can turn the narrative away from feeling inadequate to feeling confident.

Then there's social jealousy, like if your daughter didn't get invited to a sleepover, which causes feelings of insecurity or inadequacy. "Some children have an understanding of fairness that creates an inner struggle for them when a situation occurs that displays how something can be unfair," says Dr. Zeltser.

The first rule of thumb for tackling social jealousy is to never discount your child's feelings. After all, while you might not think drama over cafeteria seating is an issue, it might mean the world to your kid. Once your child starts spilling the beans about what's bothering them, be understanding. Try saying, "I can see how that would make you feel left out." Then, problem solve by offering real suggestions to help your child overcome those jealous feelings, such as (even with the girl who left your daughter out), or joining a new club or team at school to build more friendships.

There's another kind of jealousy with young children that involves thinking you will lose or have lost some affection, attention, or security from another person because of someone or something else, including their interest in an activity that takes time away from you. This can even show up in tiny moments, like fighting for the biggest slice of birthday cake at a friend's party.

Step Three: Make things easier

When jealousy shows up, especially in social or sibling situations, it helps to set your child for success ahead of time. If you know a potentially triggering event is coming-like a sibling's birthday or a playdate they weren't invited to-give them a heads up.

If your child is already starting to feel jealous, it's important to acknowledge their feelings.

"You want to validate their emotions and acknowledge them," says Dr. Zeltser. "I see you're upset about the cake" and "Sometimes we don't get what we want"-the key is to never start the next sentence with the word "but" as you're implicitly invalidating their feelings.

Follow up with "and" instead-"And it's normal to want the biggest slice of cake. Today we're going to let your friend have it because it's his birthday." Then, shift the focus to something that would make your , like asking your child to tell their friend how much fun they are having.

Comments