The iceberg A23a did not exactly smack into the remote wildlife-rich island of South Georgia.

It was bearing down on the small British overseas territory at a glacial 1km per hour.

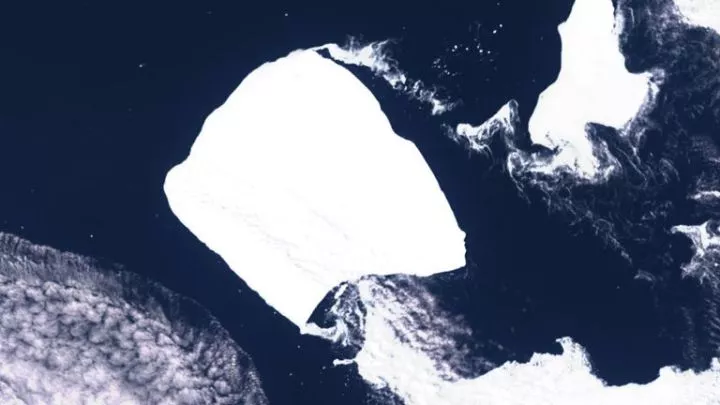

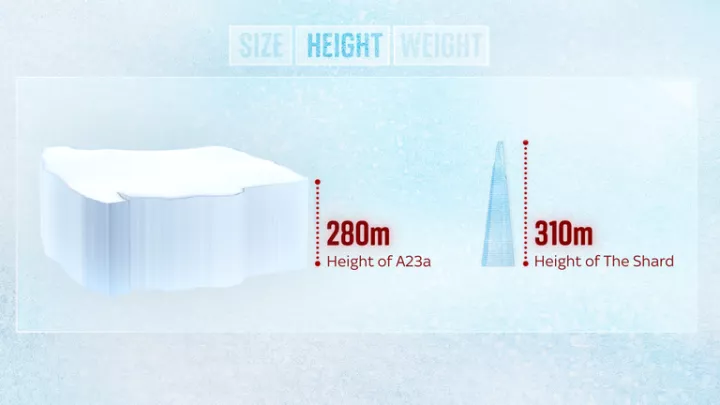

But given this megaberg is 40 miles across and weighs around five times Mount Everest, its running aground on the rocky shelf around had quite the impact.

How will it affect the wildlife?

The effect of a trillion tonnes of ice melting so close to one of the world's most important wildlife havens is uncertain. It could prevent many of South Georgia's millions of penguins from accessing food, and it's already interfered with ships moving through the area.

How long has it been around?

Megabergs like this big are not common. Vast slabs of ice are constantly breaking off Antarctica's ice shelves but most splinter into fragments as soon as they begin floating free in the warmer ocean surrounding the continent.

But A23a has persisted - for a long time.

It calved off the Ronne-Filchner ice shelf - a vast floating sill of ice in Antarctica's Weddell Sea - way back in 1986.

It took with it a Soviet research station, Druzhnaya I, that had been constructed on its edge.

The megaberg, hemmed in by other smaller icebergs barely moved for 20 years, then in 2020 began slowly drifting northwards.

It spent six months last year spinning in a revolving ocean current in the Southern Ocean before finally breaking free in the New Year on a collision course with the mountainous wildlife-rich island of South Georgia - 1,000 miles north of where it started.

It approached the island at a speed of around 30km a day. "Fairly ripping along for an iceberg," according to Andrew Meijers, an oceanographer at the British Antarctic Survey in Cambridge.

Will it shrink?

The sea around South Georgia is warm compared to its Antarctic birthplace, so the iceberg is expected to get thinner, more fragile and break up quite quickly.

The impacts it might have are likely to be localised - but not insignificant if you are one of the millions of penguins or seals that call South Georgia home.

A trillion tonnes of fresh water, which floats on top of more dense sea water, could force the food for marine animals deeper underwater.

Alternatively, if the megaberg is carrying a lot of mud and sediment, this could add nutrients to the water, providing more food for sea life.

What are the consequences?

A23a is symbolic of a more global and far more consequential trend: the rapid melting of ice in Antarctica.

The continent is losing around 150 billion tonnes of water in the form of ice a year, half carried away as icebergs, the rest due to ice melting directly off the continent itself.

As the world's largest reserve of fresh water, this is leading to the inexorable rise in sea level - expected to be around 60cm by 2100 - due to Antarctic melting alone.

But a more pressing concern is the impact of all that fresh water on the Antarctic Circumpolar Current - a slow overturning of ocean water that serves as our planet's cooling system.

Warm air from the rest of the planet heats the surface waters, currents then draw this warmer water down, replacing it with cooler water from the depths of the ocean.

"It does all of the heavy lifting in terms of trapping heat from global warming," says Dr Meijers.

Microscopic plants - phytoplankton - in the region also absorb the most planet-warming carbon dioxide which is, like the warmer water, carried deep into the oceans and stored there.

A recent study suggests fresh water from melting icebergs and the Antarctic continent is already slowing this circumpolar current and may reduce its speed by 20% by 2050. A potentially worrying "positive feedback" that could further exacerbate global warming.

Comments