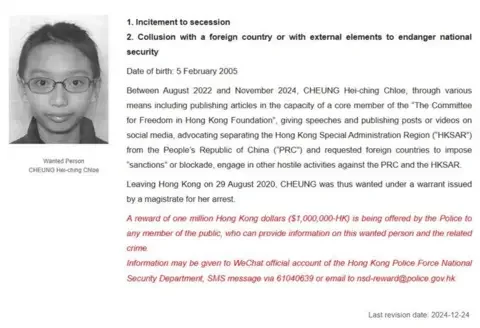

Just over a year ago, Chloe Cheung was sitting her A-levels. Now she's on a Chinese government list of wanted dissidents.

The choir girl-turned-democracy activist woke up to news in December that police in Hong Kong had issued a $HK1 million ($100,000; £105,000) reward for information leading to her capture abroad.

"I actually just wanted to take a gap year after school," Chloe, 19, who lives in London, told the BBC. "But I've ended up with a bounty!"

Chloe is the youngest of 19 activists accused of breaching a national security law introduced by Beijing in response to huge pro-democracy protests in the former British colony five years ago.

In 2021, she and her family moved to the UK under a special visa scheme for Hong Kongers. She can probably never return to her home city and says she has to be careful about where she travels.

Her protest work has made her a fugitive of the Chinese state, a detail not lost on me as we meet one icy morning in the café in the crypt of Westminster Abbey. In medieval England, churches provided sanctuary from arrest.

Hong Kong officials issued the warrant for Chloe on Christmas Eve, using the only photo they appear to have on file for her - in which she is aged 11.

"It freaked me out at first," she says, but then she issued a public response.

"I didn't want the government to think I was scared. Because if Hong Kongers in Hong Kong can't speak out for themselves any more, then we outside of the city - who can speak freely without fear- we have to speak up for them."

Chloe attended her first protests with her school friends, in the early days of Hong Kong's 2019 demonstrations. Protesters turned out in huge numbers against a bill seen as extending China's control over the territory, which had enjoyed semi-autonomy since Britain handed it back in 1997.

"Politics were never in my life before... so I went to the first protest with curiosity," she said.

She saw police tear-gassing demonstrators and an officer stepping on a protester's neck.

"I was so shocked," she says. "That moment actually changed how I looked at the world."

Growing up in a city that was part of China but that had retained many of its freedoms - she had thought Hong Kongers could talk about "what we like and don't like" and "could decide what Hong Kong's future looked like".

But the violent crackdown by authorities made her realise that wasn't the case. She began joining protests, at first without her parents' knowledge.

"I didn't tell them at the time because they didn't care [about politics]," she says. But when things started to get "really crazy", she browbeat her parents into coming with her.

At the march, police fired tear gas at them and they had to run away into the subway. Her parents got the "raw experience", she says, not the version they'd seen blaming protesters on TV.

Afters months of demonstrations, Beijing passed the National Security Law in 2020. Suddenly, most of the freedoms that had set Hong Kong apart from mainland China - freedom of expression, the right to political assemblies - were gone.

Symbols of democracy in the city, including statues and independent newspapers, were torn down, shut or erased. Those publicly critical of the government - from teachers to millionaire moguls like British citizen Jimmy Lai - faced trials and eventually, jail.

In response to the crackdown, the UK opened its doors to Hong Kongers under a new scheme, the British National Overseas (BNO) visa. Chloe's family were some of the first to take up the offer, settling in Leeds, which offered the cheapest Airbnb they could find. Chloe had to do her GCSEs halfway through the school term, and during a pandemic lockdown.

At first, she felt isolated. It was hard to make friends and she had trouble speaking English, she says. There were few other Hong Kongers around.

Unable to afford international student fees of more than £20,000 a year, she took a job with the Committee for the Freedom of Hong Kong, a pro-democracy NGO.

When China started putting bounties on dissidents' heads in 2023, they targeted prominent protest leaders and opposition politicians. Chloe at the time, still finishing her A-levels, thought was she too small-fry to ever be a target.

Her inclusion underlines Beijing's determination to pursue activists overseas.

The bounty puts a target on her back and encourages third parties to report on her actions in the UK, she says.

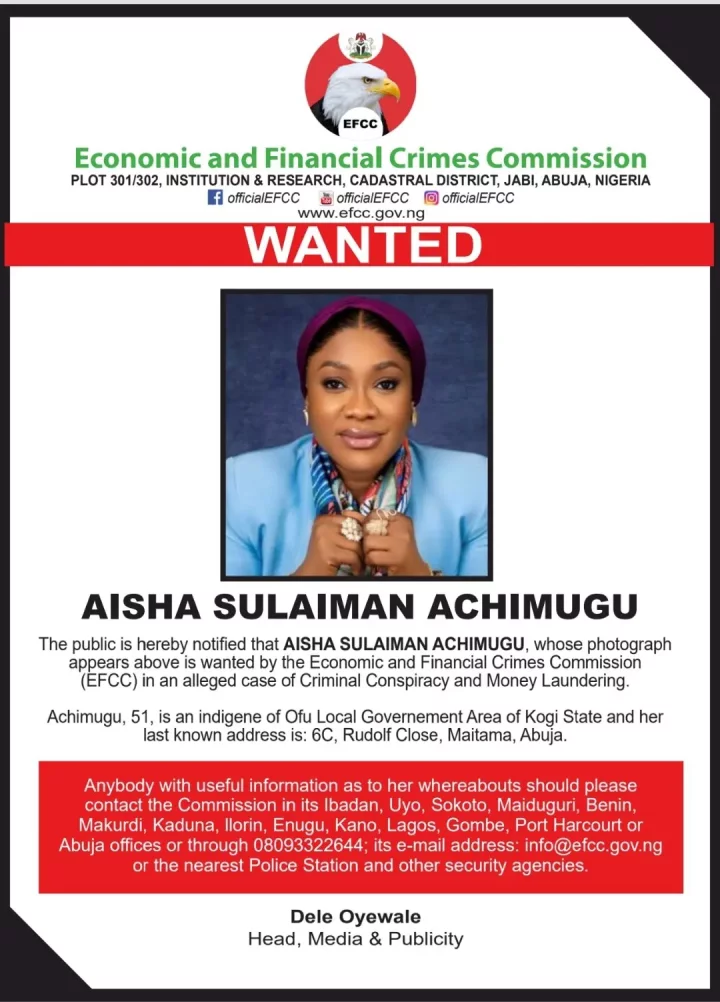

China has been the leading country over the past decade trying to silence exiled dissidents around the world, according to a report this week.

Another Hong Kong dissident who reported being assaulted in London blamed the attacks on Chinese government-linked actors.

And last May, British police charged three men with gathering intelligence for Hong Kong and breaking into a home. One of the men was soon after found dead in unclear circumstances.

"They're only interested in Hong Kongers because they want to scare off others," Chloe says.

She says many of those who've moved over in recent years stay quiet, partly because they still have family in Hong Kong.

"Most of the BNO visa holders told me this because they don't want to take risks," she says. "It's sad but we can't blame them."

Advertisement

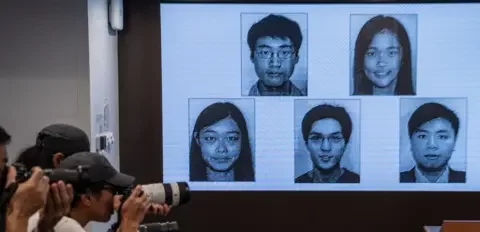

Bounty targets

July 2023: Eight high profile activists are named including:Nathan Law, Anna Kwok and Finn Lau, former politicians Dennis Kwok and Ted Hui, lawyer and legal scholar Kevin Yam, unionist Mung Siu-tat, and online commentator Yuan Gong-yi.

December 2023: Simon Cheng, Frances Hui, Joey Siu, Johnny Fok and Tony Choi

December 2024: Tony Chung, Carmen Lau, Chung Kim-wah, Chloe Cheung, Victor Ho Leung-mau.

On the day her arrest warrant was announced, Foreign Secretary David Lammy said the UK would not tolerate "any attempts by foreign governments to coerce, intimidate, harass or harm their critics overseas". He added the government was committed to supporting Hong Kongers in the UK.

But more needs to be done, says Chloe, who's spent the first weeks of this year lobbying Westminster.

In the past fortnight she has met Prime Minister Keir Starmer at a Lunar New Year event at Downing Street, and shadow foreign secretary Priti Patel, who later tweeted: "We must not give an inch to any transnational repression in the UK."

But she worries whether the UK's recent overtures to China could mean fewer protections for Hong Kongers.

"We just don't know what will happen to us, and whether the British government will protect us if they really want to protect their trade relationship with China."

Does she feel scared on the streets in London? It's not as bad as what political activists back home are facing.

"When I think of what [they] face... it's actually not that big a deal that I got a bounty overseas."

Comments