Taliban say access to climate funds is the right of their people. But experts tell Stuti Mishra that giving them a seat at the table might be seen as legitimising their human rights abuse

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

The Taliban's demand for access to global climate finance amid Afghanistan's worsening droughts, floods, and food insecurity has sparked a global dilemma: will the hardline regime's inclusion be seen as legitimising their brutal curbs on women and girls?

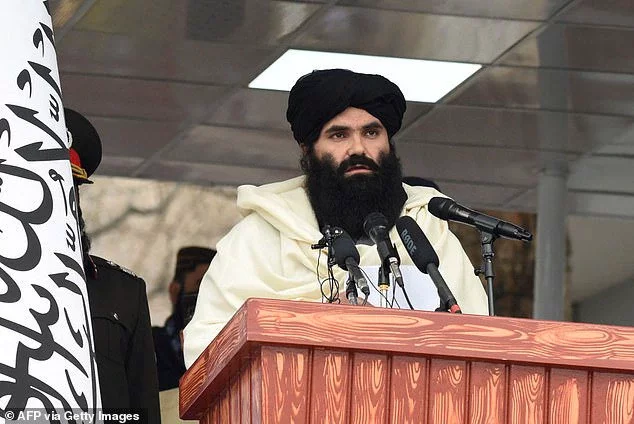

At the recent Cop29 in Baku, the Taliban delegation attending as observers for the first time since 2021, made their case for a full party status in future climate negotiations and access to international climate funds.

"It is the right of our people, who are among the most vulnerable to climate change," Mutiul Haq Nabi Kheel, the National Environmental Protection Agency (NEPA) chief, tells The Independent. "We should not be invited as guests [in the next COP] but as full participants."

The plea comes as Afghanistan endures relentless climate disasters. Earlier this year, flash floods in Ghor and Badakhshan swept through villages, killing dozens, displacing thousands, and washing away farmland. Prolonged droughts left over 12 million people, nearly a third of the population, facing severe food insecurity. The climate crisis has pushed the country, which contributes less than 0.1 per cent of global emissions, into a devastating cycle of drought, floods, and hunger.

The Taliban's return to the climate stage has sparked a debate on whether the world can deliver aid to Afghanistan without recognising a regime that stands in direct opposition to human rights values. Any participation by the Taliban has led to a global pushback in the past.

When the de facto rulers sent officials to Qatar this year for a meeting with UN officials, Human Rights Watch said the move could do "irreparable harm to the UN's credibility as an advocate for women's rights and women's meaningful participation".

The concerns persist as the Taliban continue to isolate women from public life, even closing the last few remaining avenues of work such as paramedical and midwife training recently. In a 2023 report, Amnesty described the Taliban's actions as "relentless and targeted oppression of women and girls".

Yet the worst brunt of Afghanistan's exclusion from climate finance, which has stalled critical projects that could mitigate the worst impacts of the climate crisis, has also been borne by its most vulnerable people.

Humanitarian groups and climate experts argue that inaction is punishing the Afghan people, not their rulers. "Try explaining to an Afghan woman how you're helping her by holding back," says Graeme Smith, senior consultant for Crisis Group. "If she sees her crops failing and her children going hungry, she doesn't care about global politics, she cares about survival."

Before the Taliban's return to power in August 2021, the country had access to international funds such as the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and the Adaptation Fund. However, the Taliban's lack of international recognition halted these flows overnight.

"About $2.8bn worth of ongoing infrastructure work just stopped," Smith says. "Water projects, irrigation systems, they're sitting out there, rusting in the desert."

This funding freeze has left the international community reliant on UN agencies and NGOs to deliver climate-related aid through humanitarian channels. However, experts warn that these efforts, while essential, are piecemeal and lack the scale needed to address the challenges.

Srikant Misra, Afghanistan director for ActionAid, describes the shortfall in disaster preparedness: "In Ghor, we saw floods wipe out entire villages because people had no time to respond. Simple measures like check dams, flood barriers, or rain gauges could have saved lives. But there's no funding for even these basics."

Misra says the lack of community education, particularly in rural areas, increases the risks. "When rains or snow come heavily, people don't know how to react. Communities have no tools or information to anticipate disasters."

For Afghan women, the consequences are disproportionately severe. "When disasters strike, women suffer the most," says Shahin Ashraf of Islamic Relief. "They cannot access markets to buy food, and the rising costs of essentials like flour make survival even harder for families led by women."

Despite the Taliban's limited technical capacity and resources, they have attempted to address some of Afghanistan's environmental challenges. Projects like the Kush Tepa Canal, which aims to provide irrigation to thousands, have been touted as key initiatives. Yet experts are skeptical of their effectiveness.

"They dug a trench in the desert," Smith says, "but without technical expertise and funding, it's unclear whether this will deliver long-term benefits."

At the same time, climate adaptation requires national-level coordination, a challenge in Afghanistan, where the Taliban's international isolation has left the government out of key discussions.

Smith explains that isolated, small-scale projects cannot replace the coordinated infrastructure planning needed to tackle floods, droughts, and water management. "Water flows across districts, across borders. Without a national plan, what are we really solving?"

The Taliban's observer status at Cop29 was a start, but securing full party status at Cop30 in Brazil next year will be far more contentious.

The symbolic weight of such recognition, coupled with access to funds like the GCF, would put many governments in a political bind.

"Western decision-makers are held accountable by voters and social media outrage," Smith explains. "If money flows into Afghanistan and the Taliban cuts ribbons on new infrastructure projects, the backlash could be immense, even if the funding saves Afghan lives."

Despite this, humanitarian organisations stress that the international community cannot afford to ignore Afghanistan's worsening climate crisis.

"This is not just about responding to disasters," Misra says. "It's about preparing communities for a future that's already here, building infrastructure, supporting farmers, and empowering women."

Afghanistan's vulnerability to the climate crisis is compounded by decades of war and instability, which have eroded institutional capacity at every level. In villages across the country, families face impossible decisions. As droughts persist, crops fail, and floods destroy homes, the absence of resources leaves entire communities without a path forward.

Experts argue that solutions exist. While direct funding to the Taliban remains politically unpalatable, alternatives, such as channeling funds through UN agencies, NGOs, or regional partnerships, could allow critical work to resume.

"The people of Afghanistan cannot wait for political solutions," Ashraf says. "We cannot punish women and children for the actions of a government they did not choose."

Smith believes the focus must remain on results, not optics. "Climate change doesn't care about politics. It's hitting Afghanistan harder than almost anywhere else. If we're serious about helping Afghan women and children, we have to find a way to act."

Comments