A long time ago, on the island of Flores in Indonesia, there lived strange, small-statured humans who dwelled among giant storks and shrunken elephants.

When researchers first introduced Homo floresiensis to the world twenty years ago this month, the ancient human relative sounded like something out of a fantasy novel, an unusual being living in a "lost world" surrounded by odd critters. At the time, Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings films had popularized the iconic, short heroes from the fantasy series, and Homo floresiensis' size quickly garnered the nickname "the hobbit."

But after two decades of research, and no small amount of controversy, we can be sure that Homo floresiensis wasn't really anything close to a short human with big feet and a penchant for seed cakes. Our ancient evolutionary cousins on Flores represent a unique lineage who lived during a time multiple human species were spreading to different parts of our planet, and this enigmatic relative of ours continues to puzzle scientists today.

Who discovered the 'hobbit' fossils?

The scientific story of H. floresiensis began in 1999. Archaeologists were interested in how ancient people ventured from Asia to Australia and whether Flores could have been a pitstop as our species island hopped across the Pacific. A cool cave among the forested highlands of Flores called Liang Bua seemed like a perfect place to look for evidence of people living on the island. Near two rivers, the cave had stone suitable for making tools and looked like just the sort of place that ancient people might settle.

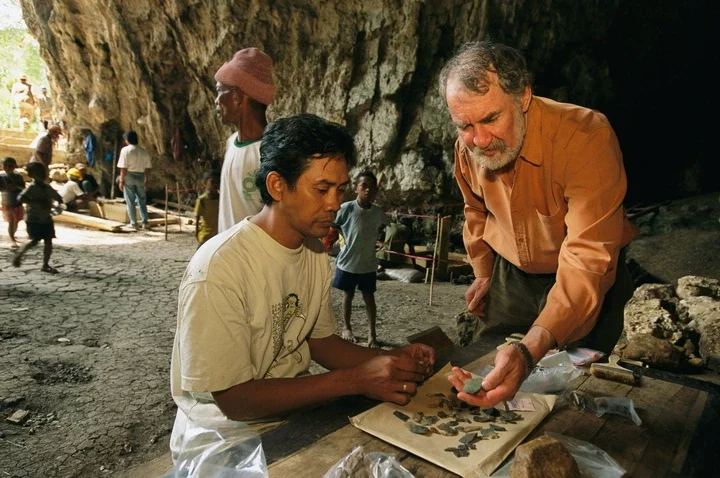

Excavations began two years later. Experts soon began finding the bones of the extinct elephant Stegodon, a giant stork, rodents, and even Komodo dragons. Then, in 2003, the researchers turned up something curious.

The lore of the discovery goes that while excavating a cave sediment laid down in the Pleistocene epoch, a local field worker found human skull bones. Wahyu Saptomo, an archaeologist with the Indonesian National Research Centre for Archaeology (Arkenas), was supervising the dig that day and recalled to the South China Morning Post in 2018, "I knew whatever this was, it was important."

Saptomo rushed to deliver the news to Thomas Sutikna, the archaeologist in charge of the excavations who was down with a fever at a hotel when the skull was found. Sutikna told Nature in 2014 that his fever immediately vanished. When he returned the next day to rejoin the crew, the team came up with a plan to remove the fragile remains without damaging them.

YEAR-LONG ADVENTURE for every explorer on your list

FREE limited-edition frog drawstring bag with every Nat Geo Little Kids Book Bundle subscription

Based on the skeleton, the individual stood just over three feet tall and would have weighed around 35 pounds. Labeled LB1 by the scientists, the fossil was also given the affectionate nickname "Flo." Such small bones initially made researchers think they belonged to a child. Quickly, however, it became apparent that the team had found something very different, and nailing down the ancient individual's identity was the first big mystery.

Who were these 'hobbits'?

The bones' age raised questions immediately. An old geologic report put them in a rock layer from 18,000 years ago, well after modern humans emerged around 300,000 years ago in ancient Africa. Closer examination of the bones nixed their connection to a modern human child. The fossils were from a species of human never seen before, one that more closely resembled the earliest members of our genus Homo from two million years ago rather than other Ice Age humans such as ourselves and the Neanderthals. In 2004, the Liang Bua team officially named the small human relatives Homo floresiensis.

Controversy soon overshadowed the unexpected discovery. Late in 2004, Indonesian anthropologist Teuku Jacob removed most of the recovered H. floresiensis material from the collections of Jakarta's National Research Centre of Archaeology. Jacob maintained that the bones represented modern humans with developmental disorders, not a different human species, and rumors spread that the fragile bones had not been removed according to scientific standards. Eventually, a few months later, Jacob returned the bones. Several were damaged sometime during their transport back and forth between the labs, the Liang Bua team and Jacob disagreeing over what had transpired. The scandal was so intense that officials in Indonesia closed access to Liang Bua for two years.

The renewed explorations of the cave turned up even more H. floresiensis fossils. By 2015, archaeologists had found the remains of at least 15 early humans at the site. Updated radio carbon dating placed the hominins in Liang Bua Cave between 60,000 and 100,000 years ago, and stone tools from another site suggest that the ancient humans arrived on the island at least one million years ago. Another study published in August affirms that small humans lived on Flores by 700,000 years ago.

The discovery of additional H. floresiensis fossils has been essential in working out the identity of these ancient humans. Like Jacob, some experts have suggested that the bones from Liang Bua represent modern humans with different medical conditions, such as microcephaly or down syndrome, that would cause their small size and skull shape. But skeletons of H. floresiensis individuals share very consistent traits, the marker of a different species rather than disease or injury. What anthropologists continue to puzzle over, however, is how these ancient humans arrived on Flores and where they fit on the evolutionary tree.

Where did the 'hobbits' come from?

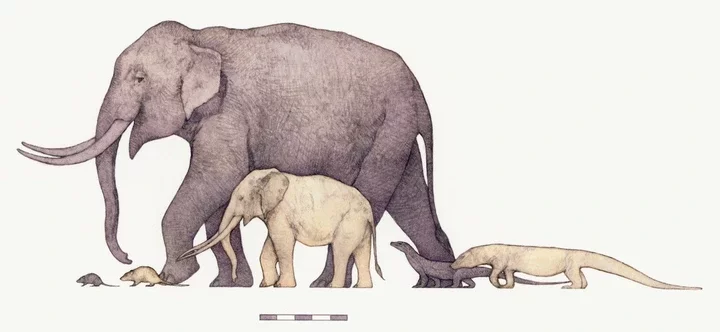

Initially, the Liang Bua team thought that H. floresiensis had descended from a population of an earlier human relative, Homo erectus, that shrunk during their isolation on the island. Homo erectus was one of the earliest human species to venture out of Africa around two million years ago and had made it to Indonesia before dying out around 110,000 years ago. The extreme nature of other fossils found at Liang Bua seemed consistent with what biologists call the island effect, where island animals get either smaller or bigger. Smaller geographical area, a lack of large mammalian predators like big cats, and other factors are thought to drive these unusual evolutionary shifts. H. floresiensis seemed to indicate that humans were subject to the same phenomena in isolation.

The oldest fossils of H. erectus in the region, however, are about as old as the oldest H. floresiensis. And when some anthropologists have looked at the bones of the Flores humans, they see signs of much older humans. The feet, wrists, and other parts of the H. floresiensis skeleton more closely resemble even older human relatives from about 2 million years ago, such as Australopithecus species and Homo habilis, hinting that the Flores humans represent an early human lineage that somehow made it to Indonesia. To date, however, anthropologists haven't found such early human fossils outside of Africa. Both hypotheses have their own snags, awaiting future discoveries to fill in the backstory of the short humans.

"Those that think that Homo floresiensis is a descendant of Homo erectus think that they are small due to island dwarfing," says Matt Tocheri, an anthropologist at Lakehead University in Canada who has studied the fossils. The problem is that there is no sequence of fossils showing H. floresiensis or their ancestors becoming smaller over time. "Others, like myself, are more open to the idea that H. floresiensis might be small because their early hominin ancestors may have been small-bodied and small-brained to begin with," Tocheri says, but acknowledges that this alternative still requires fossil evidence of such early humans outside Africa.

What else lived on this island?

Even as experts await additional discoveries to resolve the origin of H. floresiensis, analysis of the cave and its broader fauna have helped fill in what the world of the Flores humans must have been like.

Finding an early human on a tropical volcanic island had been surprising to the scientific community. "Flores had an unusual ecology compared to other areas with fossil hominins, like Africa," says Hanneke Meijer, a paleontologist at the University of Bergen in Norway. The island's dense forests were far different from the classic images of early humans striding across east African grasslands. Ancient Flores was home to small elephants, big lizards, and other unusual creatures, animals that H. floresiensis was undoubtedly intimately familiar with.

Fossil birds are among the most useful fossils for drawing out the ecology of prehistoric Flores. "Birds can give us very useful information about the environment, the vegetation, and the dynamics between species within an ecosystem," Meijer says.

At nearly six feet tall, the giant stork Leptoptilos robustus would have towered over H. floresiensis. While not exceptionally large compared to other fossil storks, the bird was one of the larger flesh eaters on the island and likely hunted the island's rodents and visited the carcasses of larger animals such as Stegodon. "Giant storks and vultures were dependent upon Stegodon for food, as were the Komodo dragons and H. floresiensis," Meijer says, meaning several species were all reliant on the elephants for meals. When the elephant went extinct, it caused a cascading effect that might explain the disappearance of the carnivores, including H. floresiensis, from the island. "For me, this drives it home that the hominins were just a part of a much larger ecosystem," Meijer says.

What we still don't know about Homo floresiensis

Despite all that anthropologists have learned, it's still unclear how exactly these ancient humans found themselves on Flores and why they disappeared. Uncovering answers will require understanding the human not as a strange singularity in human history, but as an interconnected part of the ancient world. "I think we can only understand the evolution of H. floresiensis within the context of the evolution of the Flores fauna itself, since this is the environment it arrived into and thrived in for more than 700,000 years," Meijer says. How the hominins arrived, where they came from, and what became of them are still open questions, informed by expanding research on additional sites, such as a place in the island's So'a Basin called Malahuma where Stegodon bones and stone tools have been found.

"If there was a book that had all the information that we wanted to know about H. floresiensis, then what we know about them right now would only consist of a few ripped and tattered pages with some incomplete sentences and paragraphs," Tocheri says. We know that they existed, and were different from other humans, but far more is unknown about them than we currently understand. "What did Gandalf say?," Tocheri muses, "When you think you know something about hobbits, they go ahead and completely surprise you."

Comments