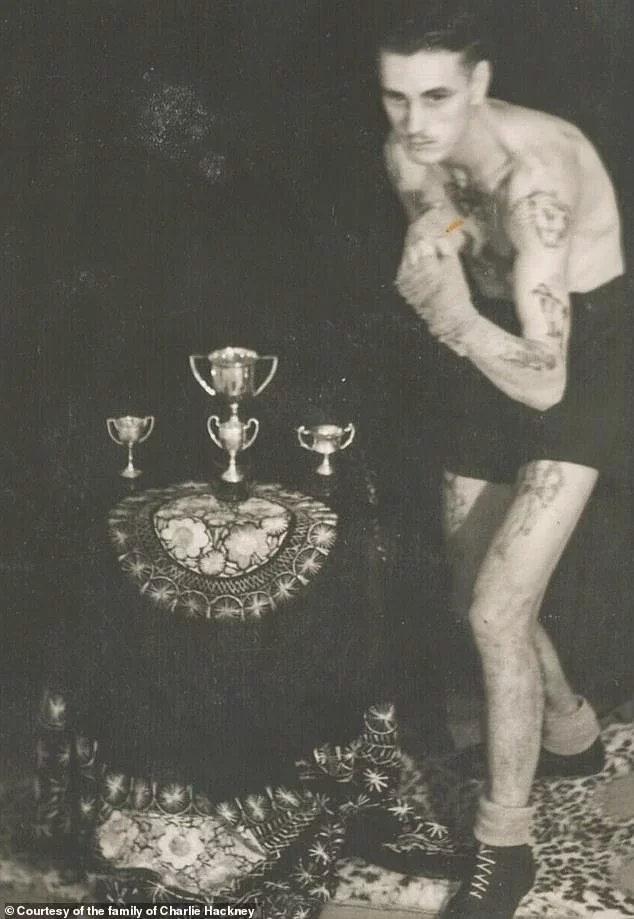

As the SAS battled their way across Nazi-occupied France, Corporal Charlie Hackney - a veteran of the unit - had settled upon a 'novel way of subverting the enemy'.

He and his self-confessed 'subdued bunch of cutthroats' from the elite regiment founded by David Stirling in 1941 had seized a red Renault butcher's van, transforming it into a battle wagon.

With a Bren light machine gun mounted in the rear 'one only had to open the doors to fire the weapon', Hackney observed, their 'little red van' proving 'far less conspicuous' than any SAS jeep.

They'd added a pair of 3-inch mortars to the vehicle's hidden arsenal and proceeded to wreak havoc behind enemy lines, at one point hitting a convoy of tankers transporting 40,000 gallons of fuel, and at another assaulting a German garrison headquarters.

Now, on April 3, 1945, Hackney and his Special Air Service comrades found themselves quartered in a deserted farmhouse near Lüneberg, a city nearly 200 miles inside Nazi Germany.

Having pressed so far ahead of the Allied lines, they'd been ordered to a halt. As they paused, Hackney had time to reflect upon the war and its dark predations.

He noted: 'We knew that somewhere in the Reich Chancellery, Adolf Hitler was trying to convince his general staff that all was not lost, that the tide would indeed turn in their favour!'

It was that which gave Hackney his big idea. If someone could make it through to Berlin, could they somehow get their hands on Hitler himself?

If they could press ahead riding in a little red butcher's van substitute - that battle wagon had long since died a death, burning itself out on a roadside - this seemed the sort of mission tailormade for the SAS.

Hackney put the idea to his subdued bunch of cutthroats. Two volunteers stepped forward. So began their 'last desperate mission of the war.'

Commandeering a German civilian car, the three adventurers set forth in the depths of night.

They'd dressed themselves in civilians clothes, to avoid being 'shot at by any desperate Nazis' along the way.

With their uniforms bundled into the boot, and their weapons concealed, a long drive to Berlin lay before them.

Making for the nearest autobahn, they banked on a four to five-hour journey across nearly 200 miles, if the motorway proved clear.

But on the outskirts of a major city the car suffered a fault. They pulled over at the roadside.

It was starting to get light, and the road was clogged with refugees, all intent on 'getting away from' the advancing Russians.

Worried that the refugees might see through their disguises, Hackney warned Jack Maybury, his deputy, to 'keep on his toes', for Maybury was the only one of them who could speak decent German.

Some of the refugees paused to chat. They began talking excitedly about a group of senior Nazis who were hiding in a nearby building.

With the car now fixed, Hackney was 'all for pushing on to Berlin,' but the others were keen to investigate the mystery house.

Outvoted, Hackney fell into line. Gathering their weapons they set off on foot to reconnoiter the house, a large old building with an extensive garden.

With the others covering the exits, Hackney stole through the front door, checking the rooms that branched off the hallway.

Silently, he started to climb the stairs. It was then he heard an odd creaking noise coming from one of the rooms below.

Slipping inside, he spied a trap-door set in the floor which was in the process of being shut. Grabbing it, Hackney levered it open, firing a couple of shots into the dark below.

He yelled into the shadows for whoever was there to show themselves or 'suffer the consequences'.

After a few seconds three figures came clambering up the steps, their hands in the air.

All were dressed as civilians, with leather jackets or greatcoats to ward off the chill.

Leaving them under the guard of his comrades, Hackney searched the cellar. It was empty apart from some old wine bottles.

Hackney explained just who they were, and that the trio were now their prisoners.

Surprisingly, the captives knew all about the SAS, who were 'held in awe' by the German military.

As Hackney went to search each of the captives, the tallest reached inside his coat and pulled out a pistol. 'Like a flash I knocked it from his hand,' Hackney remarked.

As he slipped the weapon inside his battle dress, the tall fellow seemed utterly distraught.

Speaking in broken English, he claimed that was the weapon that 'Adolf Hitler was shot with.'

Apparently Hitler had committed suicide and here was the weapon that had fired the magic bullet.

The tall captive kept pleading for its return, as some kind of a memento of the Fuhrer.

Even as this was happening, the stocky fellow was 'inching his was along the wall towards the passage.'

With the SAS men's attentions riveted by the Hitler suicide story, all of a sudden he made a break for it.

The SAS went after him, but he leapt over the back garden wall and managed to slip away.

The two remaining prisoners were taken upstairs and interrogated. Under dire threats, the taller of the two confessed that he had been present when Hitler had killed himself.

Being a doctor, he had attended to the Fuhrer's body. That was how he had come by the precious pistol.

The SAS trio remained keen to head for Berlin, to check out the story. They decided to take the captives, but the tall fellow objected vociferously, protesting 'strongly about being used' by his captors.

As the argument raged, the growl of engines were heard outside. Army jeeps had arrived, bearing the unmistakable forms of the Military Police (MPs).

The visitors turned out to be a Provost Marshall - a MP commander - plus his men. Hackney explained what they were doing there, but the Provost Marshall refused to believe a word.

British soldiers did not set forth so far in advance of the front line and especially dressed as civilians. Hackney and his men were put 'under close arrest'.

Taken to a central command building for questioning, the following day, Lieutenant-Colonel Brian Franks, a senior SAS commander, arrived, to verify the captives' bona fides.

Once Franks had vouchsafed for his men, they were released. Driven to the nearest SAS base, Hackney, as the commander of this rogue mission, was threatened with Court Martial.

But once he'd given a full account of his 'mad scheme', Franks began to relent. A part of him appreciated its initiative, flare and audacity.

Finally, the trio were released without charge.

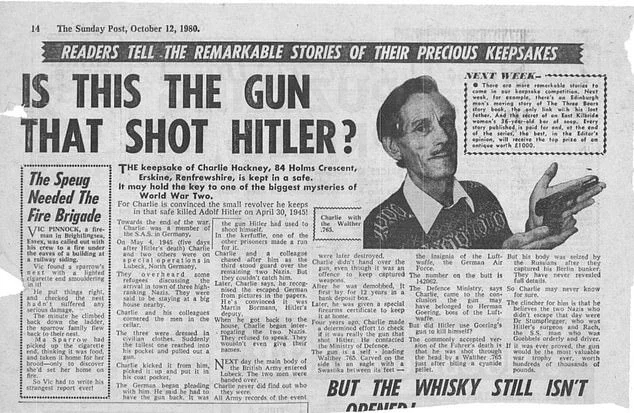

Hackney had made sure to keep the gun, always wondering if it was 'indeed the pistol which brought about Hitler's death.'

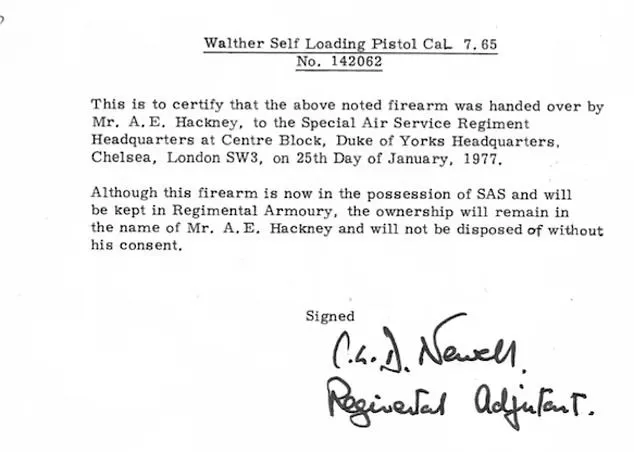

Post war, he remained deeply intrigued by the weapon - a Walther PP 7.65 mm.

Carved into the side of it was an eagle grasping in its talons a swastika, above the serial number 142062.

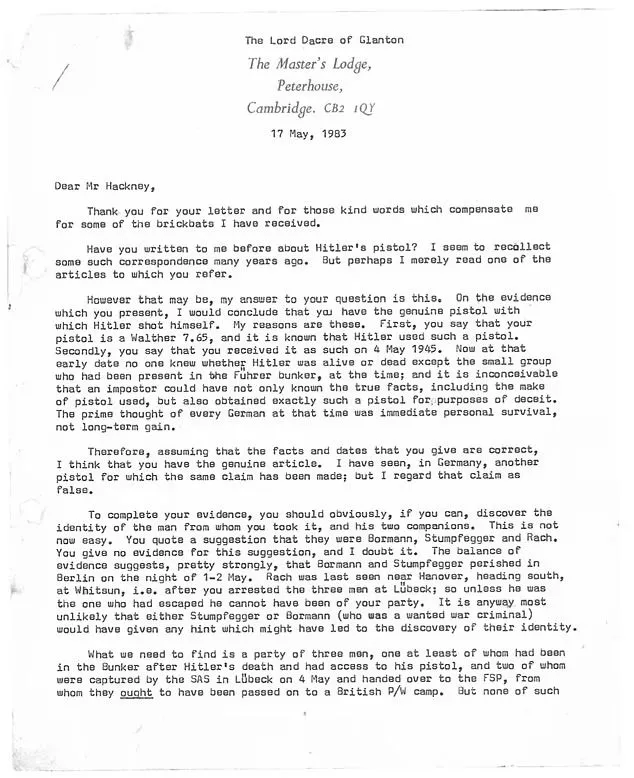

He launched a series of investigations, exchanging correspondence with the likes of Hugh Trevor-Roper, Lord Dacre of Glanton, who was then the Regent Professor of Modern History at Oxford University.

Lord Dacre, the author of hugely influential work The Last Days of Hitler, said to Hackney: 'On the evidence you have presented I would conclude that you have the genuine pistol with which Hitler shot himself.'

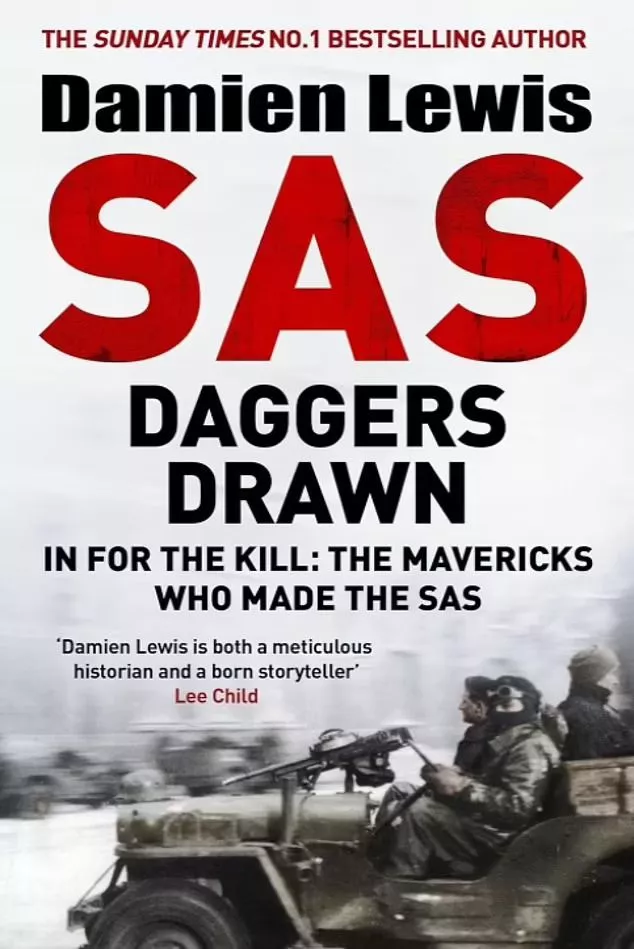

Hackney also corresponded with famous thriller writer Jack Higgins - Harry Patterson - who declared that Hackney's story was 'Very, very interesting and highly probable I should have thought.'

Higgins had just written a thriller entitled The Valhalla Exchange, about the last days of Hitler and his henchmen, and about the eleventh hour escape of some from the Berlin bunker.

Eventually, Hackney handed the pistol to the SAS Headquarters, in London, to be held in the central armoury for safekeeping.

In 1979, he asked for its return, and was told it would need to be delivered to him in person, 'for we should all be in the soup in a big way if the thing went astray.'

In 1988 he sold it to a private collector, without having been able to prove its absolute provenance.

Ten years later, Hackney would write several accounts of his wartime adventures, including the 'Hitler pistol' story.

Comments