Among the languages that enjoy significant prestige and history is obviously English. The greatness of English, ironically enough, was inherited not from the speakers it has today, and as the language of the Free World, but from its great history, a history of blood and sacrifice. So see how English stumbled its way to the modern world.

Old English: The Origins.

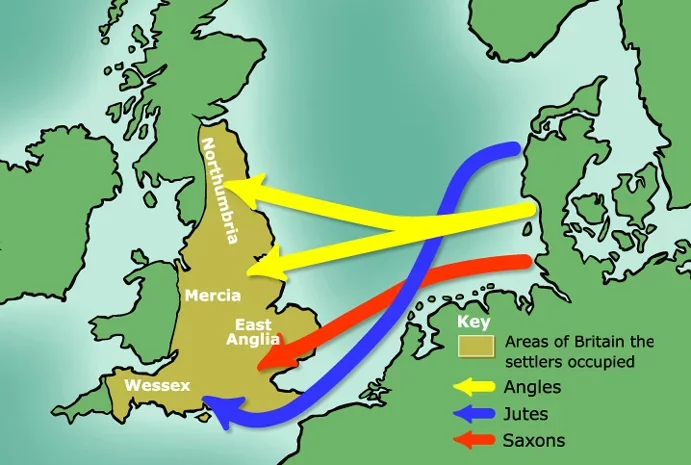

The story begins in the first millennium in Northern Germany, near Denmark. That's where the roots of English are, not in England. After the bleeding Roman Empire collapsed and left Britain in the 5th century, three tribes from Northern Germany, namely the Angles, the Saxons, and the Jutes, invaded Britain and brought their language with them. The prominent tribe, viz. the Angles, named the land after themselves, i.e. Angle-land (England) as well as the language, i.e. Angle-lish (English). The invasion also included displacing the indigenous Celts there into Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and Cornwall. This resulted in a total linguistic defeat as no trace of Celtic was left in English and it replaced Celtic as the language of England.

From the 9th well into the 11th century, the Vikings and their language invaded Britain. The linguistic defeat, luckily, was slim to none, as Old Norse (the language of the Vikings) was very similar to Old English and, aside from borrowings, the language of the Anglo-Saxons didn't change much.

Old English: French blood.

Here comes the French invasion now. In exactly 1066, William the Conqueror, or the Bastard, attacked Britain, bringing with him the Norman dialect of French, which soon became the official language of the ruling class, and the language of important business and political matters, and Old English was left for dead, but not for long.

Shortly after 1200, the Normans lost Normandy, and English staggered back up and reestablished itself as the official language of Britain. But it was not the same English; it was an English with French blood in its veins. The French influence on English is witnessed in the form of thousands of Latinate words and a variety of grammatical quirks that go with them that last to date. Here is a table of some examples:

Examples of other Latinate words include: desist, donate, vibrate, etc. These words have a restricted syntax, for example you can say "give the museum a painting" but not "donate the museum a painting", "shake it up" but not "vibrate it up". These Latinate words also trigger some unsystematic sound changes that make English morphology and spelling a little annoying, especially for those who are trying to learn English in schools. This is evident in word pairs such as electric-electricity, nation-national, respect-respectable, etc. Latinate words are also longer and more formal due to their attachment with the government, the church, and the schools of the Norman conquerors, and overusing them yields some cheesy pieces of language that many of you will deplore. You don't believe me? Compare these two sentences: "The adolescents who had effectuated forcible entry into the domicile were apprehended" versus "We caught the kids who broke into the house". What of absolute wonder is how English survived after the voracious French linguistic attack, a feat that English deserves a medal for. If it would interest you, see how English survived [here].

Middle English: Silent vowels: "HERE WE COME!"

Let's jump now right to the era in which Chaucer lived, spanning between 1100-1450; also called the Middle English period. It is in this period that really significant changes had been introduced to English. Before 1100, all syllables were articulated including those represented by what we call today silent vowel. For example, take would have been pronounced with two syllables as [theike]. In Middle English, final syllables had been reduced to the generic schwa (like the a in allow) and in many cases, they were eliminated entirely. This sound change had significant ramifications on the syntax of English. Since final syllables contain case markers, overt case started to disappear, this resulted in a fixed word order to avoid semantic and syntactic ambiguities. (So now you know why English has a fixed word order and covert case). This is not just it, prepositions and auxiliaries like of, do, will, and have were forced to lose their original meanings and were given new important and pure grammatical duties. As you can see, many of the peculiarities of today's English are the result of a simple irreversible change in pronunciation.

Early Modern English: The Great Vowel Shift.

Chaucer's time is over. Now it's Shakespeare's time and the King James bible. It's Early Modern English, bringing along all the linguistic wounds and scars that it had to endure previously, with graver scars yet to occur. The period of Early Modern English lasted between 1450 to 1700. It began with a poorly thought linguistic movement called The Great Vowel Shift, a revolution in the pronunciation of long vowels, lending English more spelling peculiarities. Some examples can be found in the table below:

Before the great vowel shift, mouse had been pronounced mooce, the "oo" turned into a diphthong. What we pronounce now as goose had been pronounced "goce". What's annoying is that spelling never bothered to track these shifts, which is why the letter a is pronounced one way in cam and another way in came, where it had formerly been just a longer version of the a in cam.

The causes of the Great Vowel Shift remain mysterious to this day. Some say perhaps that it was a way for the upper class to differentiate themselves from the lower class once Norman French became obsolete. Whatever the reason, it added more salt to the English wounds and we remain with probably the most dysfunctional spelling system across all languages. You don't agree? Riddle me this: hear /hɪə(r)/, bear (animal) /bɛər/, heard /ˈhɝrd/?. No no no! Not just these: book /bʊk/, blood /blʌd/, could /kʊd/, etc. I can go on and on, but I think I made my point. Since this was inflicted on English by its people and not by some outside linguistic attack, I'd call it friendly fire. The Great Vowel Shift, to the people living through it, felt more like the 90s trend in the Chicago area where people started to pronounce hot like hat. Or, to quote Pinker, it felt more like "the growing popularity of that strange surfer dialect in which dude is pronounced something like "diiihhhoooood"."

Anyway, English people did not wake up one day and started to pronounce their vowels or their whole language differently out of thin air. Small incremental changes piled up over long periods of times resulted in the English that we know today. So, that's in the most concise way possible the sum of important incremental changes that built up the English language, the most powerful language of all time.

What matters is that, against all odds, English pulled through. It had been the victim of multiple linguistic assaults but still managed to keep its English-y essence. For this reason, I believe English to be a living embodiment of the phrase "what doesn't kill you makes you stronger." This is a great linguistic victory worthy of so much praise.

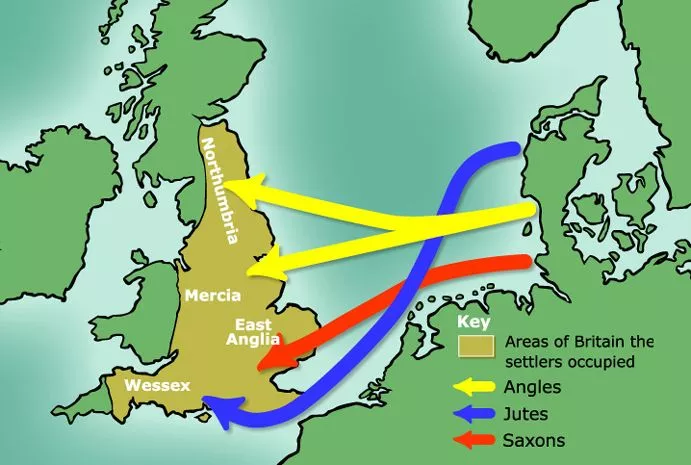

As a bonus for coming this far, here is the whole history summarized the following timeline:

Comments