When Oluyemi Orija was eight years old in Ekiti State where she grew up, the shocking murder of a farmer rocked her small community in ways she could never have imagined.

In response to the crime, police officers indiscriminately arrested about 30 farmers who owned land close to the crime scene, dragging them into the Nigerian criminal justice system without due process.

Those men remained stuck in that system for two years before they regained their freedom, largely thanks to the help of Orija's father who fought to ensure the accused got justice.

Even though she wasn't directly affected by the incident, her friend whose father was one of the arrested farmers had to drop out of school as a consequence of his unfair detention.

This was the building block of young Orija's determination to become a lawyer and help the oppressed.

In 2015, now an adult and two years into her law practice, Orija was in a courtroom in Lagos when she noticed a young man was about to be detained in prison for breaking crates of eggs during a fight. She had been in the courtroom for a different case, but quickly jumped to his defence and convinced people in the courtroom to contribute ₦5,000 for the broken eggs and prevent the defendant from going to prison to await trial, possibly for years.

"When I stepped out of the courtroom that day, it was like I was empowered," she told Pulse Nigeria. "I thought to myself, this is something I have to really do on a bigger scale," she added.

Even though it would take another four years to properly set up, that was the day the idea of Headfort Foundation formed in Orija's mind. The non-profit organisation provides free legal services for poor people stuck in prison with no legal representation.

Nigeria's justice system problem

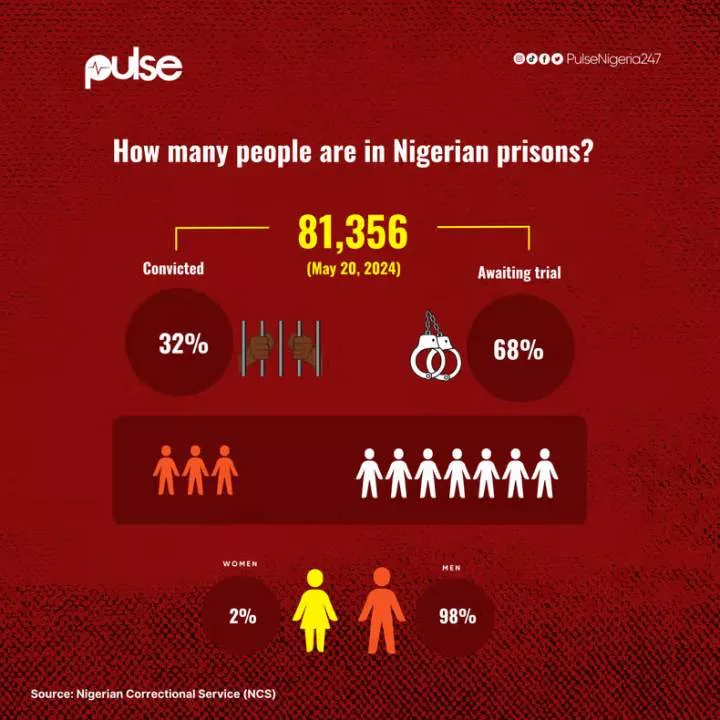

As of May 20, 2024, a total of 81,356 inmates were locked up in prisons across the country, according to public data by the Nigerian Correctional Service (NCS). But only 25,891, about 32% of them, have been convicted of a crime. The remaining 55,465 inmates, 68% of Nigeria's prison population, were being held while their cases dragged in courts.

The figure has worried officials for decades, especially since these prisons are also congested in ways that are harmful to inmates. "Within the NCS, we're advocating the issues with our stakeholders at the ministry of justice and judiciary, especially to give inmates bail and let them go pending trial," the spokesperson of the Lagos Command of the NCS, Rotimi Oladokun, told Pulse.

The reasons there's an unusually large number of awaiting-trial inmates in prison are numerous and not far-fetched. Most crucially, the pace of the Nigerian court system is so slow that cases aren't treated efficiently, according to Ikemesit Effiong, partner and head of research at SBM Intelligence.

The analyst believes Nigeria's methods of criminal justice delivery are not fit for the modern world, and that has a human cost.

"The system is overburdened, understaffed, under-resourced, and some of our justice delivery practices don't incentivise speedy resolution of cases," he noted.

He cautioned that Nigerians should not be comfortable with a system that perpetuates an environment in which innocent people are trapped for years before they can access justice.

For example, in 2017, Segun Esan, a 36-year-old father of three, ended up inside a police cell because he was riding his motorcycle around 10 pm when police officers decided it was too late to be outside. He was then moved to the custody of the now-dissolved Federal Special Anti-Robbery Squad (FSARS) where he was detained, and arraigned in court three months later for being a thief.

It took the prosecution's key eyewitness five years to make it to court, only to testify that Esan was not responsible for what he'd been accused of. The painter spent more than six years at the Kirikiri Maximum Prison in Lagos, missing the first six years of his third child's life, for nothing.

"I have lost a lot," he told Pulse after his release from prison. "If I had been free since 2017, I know what I would have achieved with the work of my hands."

Similarly, 27-year-old Ibukun Ajigbotesho ended up in a police cell after he was arrested inside his aunt's living room and accused by the police of stealing three motorcycles with his friend. The transport worker remained in prison for over three years because his family could not afford the ₦100,000 bail set by the court.

In 16 court appearances throughout his incarceration, the court only sat four times. Sometimes, the judge was unavailable, or there was no light in the courtroom and no fuel to operate the generator.

"Judges should be a bit more sensitive. How can you not show up on a date you adjourned a case, not once but many times? It feels like you're just making people suffer," he lamented to Pulse.

How Headfort is helping

Esan and Ajigbotesho could possibly still be behind bars if Headfort had not found them and fought for them. Since it launched in 2019, the foundation, a non-profit subsidiary of Headfort Chambers, has been directly responsible for getting over 600 people out of prisons in multiple states.

Many of its beneficiaries are poor people who would have otherwise struggled to find such help. Headfort lawyers typically visit police and court cells to look for detained suspects who don't have legal representation. Upon evaluating cases, the team puts together a defence strategy to help get wrongfully detained defendants out of prison.

"What has stood out for me is many Nigerians, regardless of their education status, really do not know their rights. I believe if people know their rights and how to handle issues starting from the police station, many people will not even get to prison in the first place," Orija noted.

Fighting an entrenched criminal justice system is bound to come with its challenges and the Headfort team knows that all too well, according to its founder.

At its core, the problem is institutional, especially at the point of entry where the police are the gatekeepers. Outside of the well-documented history of abuse of power by officers, Orija believes Nigerians are also guilty of empowering them by involving them in civil cases. But things don't end there.

When cases get to courtrooms, even judges can sometimes be powerless to step in even when they can recognise cases that have no legal substance, according to the lawyer.

It's also entirely possible that defendants in court have a trial without proper legal representation, or sometimes do not even understand English, like Esan. It's easy to end up in a Nigerian prison for years if one or a combination of these factors happens.

Orija enjoys the work Headfort does and wants to expand all over the country, with the help of donations from well-meaning supporters, but her big-picture goal isn't to keep plugging holes forever.

She'll keep doing the work as long as it's necessary, but she'd rather the government identify all the gaps and fix the institutional problems. This multipronged solution also includes the public knowing what to involve the police in. The lawyer also encouraged lawmakers to amend laws and make new ones that benefit everyone who encounters the system.

"We all have a role to play," she said.

Comments