![Mass funeral of some of the victims of the Titanic [Getty] Mass funeral of some of the victims of the Titanic [Getty]](https://static.netnaija.com/i/5PKDoMndNnM.webp)

The story of the Titanic usually ends with the ship sinking in April 1912, the rescue of a handful of survivors, and the ensuing scandals and revisions to safety procedures on ocean liners.

But what about the bodies of the disaster victims? Most of the more than 1,500 victims were lost in the North Atlantic. The crews of four search ships pulled only 337 bodies from the water.

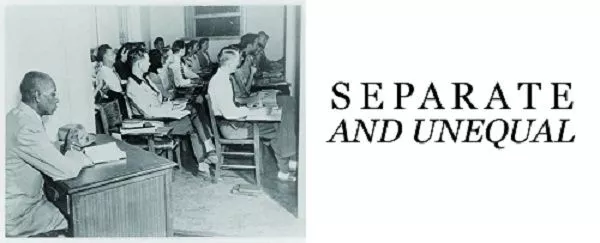

It turns out that ideas about economic/social class influenced decisions about which bodies would be buried on land and which would be returned to the icy waters of the Atlantic.

Sociology Ph.D., Jess Bier, from Erasmus University Rotterdam examined what was done with these bodies and explains how their identification and burial were linked to their economic valuation.

All the dead found were numbered for the records, but some counted much more than others. As he notes, "Decisions about which bodies to bury at sea were made largely based on the perceived economic class of the victims found, and the bodies of those with third-class tickets had a much greater chance of being returned to the water."

The microcosm of class differences on the Titanic is under fire today. "From allegations that some third-class passengers in the stern were locked below decks to that first-class passengers had a greater chance of survival, such distinctions were considered a natural part of society," Bier writes.

Class distinctions seemed to extend beyond death as well. Bier contrasts the embalming and burial on land of wealthy victims with the rapid decomposition and burial at sea of the less wealthy. About a third of the recovered bodies, about 114 of them, were thrown into the same waters from which they were pulled.

The relatively new idea of life insurance has given some bodies a monetary value. Wealthier passengers "would almost certainly have life insurance policies that would cover the costs of their burial or cremation." The working and middle classes were much less likely to have life insurance. Even if that was the case, Bier explains, "an identifiable body had to be found in order for the deceased's family to receive the life insurance payout." However, because burial at sea was dependent on class, the families of third-class victims were less likely to receive the body of their loved one.

There were, Bier writes, two criteria for storing bodies for burial on land. The bodies "had to be classified as easily identifiable, either as individuals or even as human beings" (days spent in the water and bleaching by the sun made the remains look very bad). Second, the bodies had to have "economic value even after death, with high social or economic value."

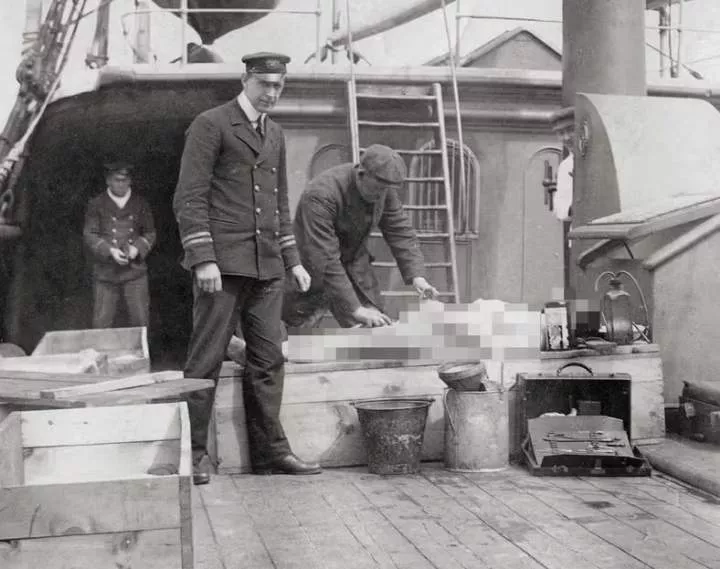

The MacKay-Bennett cable ship did most of the work involved in recovering the bodies of the Titanic disaster victims. Built for laying and repairing transatlantic cables, the ship was provided in Halifax, Nova Scotia with a chaplain, an embalmer, one hundred coffins, one hundred tons of ice, and, it was assumed, plenty of embalming fluid. However, this was not the case.

The bodies were numbered as they were brought on board. Physical features, clothing, distinctive signs and personal items were documented. Personal belongings were stored separately, marked with the same body number, and valuables were kept under lock and key. Due to insufficient materials or space to handle the bodies and their belongings, the crew had to segregate them.

First and second class passengers, identified as such by available marks, were embalmed. First-class bodies received wooden coffins; second-class bodies were wrapped in linen and kept separately. The bodies of third-class passengers and crew members were not embalmed, but simply wrapped in linen and kept on board, then buried at sea in group ceremonies.

"No significant person has been buried in the depths," Captain Mackay-Bennett said. "It seemed best to bring the dead back to land, where death could raise questions like how much insurance, inheritance, and all the litigation."

Many artifacts recovered from bodies buried at sea were cataloged and brought to Halifax, where they were then burned as unclaimed property. This was the final erasure of evidence of the existence of some passengers. Meanwhile, $5 million of the ship's insurance was paid out within 30 days of the sinking.

Bier writes that the search for Titanic victims "played a role in future body identification practices, which began to be standardised only after World War II." All this, of course, happened before DNA analysis, which has since been used more than once to identify disaster victims and clarify doubts.

Comments